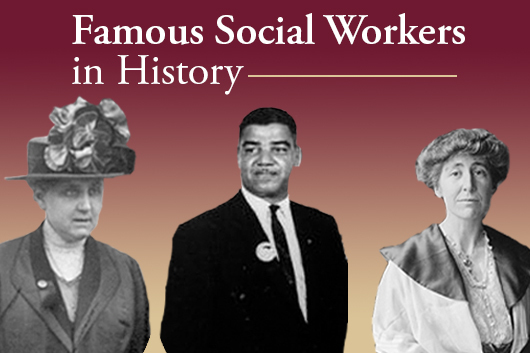

Famous Social Workers in History

The month of March marks the annual celebration of the monumental impact that social workers make on those they serve. This year, the theme for Social Work Month is “The Time is Right for Social Work” — an apt statement as social workers continue to evolve and campaign for the evolving needs and challenges facing society.

There is no better place to enter into the spirit of this year’s theme than reflecting on the generations of social workers who have led us to where we are today. Learning about the progress made by famous social workers in history reminds us why social work matters so much in the lives of individuals, communities, and society. The strength, accomplishments and stories of these social work pioneers are the foundation that current social workers build upon as they look towards the future full of possibility.

Consider the lives and legacies of seven key men and women in the history of social work whose commitment to improving the lives of others still makes a positive difference in the world today.

Harris & Ewing. (1913). Julia Lathrop, Jane Addams, and Mary McDowell in Washington, 1913, on a suffrage mission on Capitol Hill [Photograph]. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Retrieved from the Library of Congress online database.

The Mother of Social Work: Jane Addams (1860 – 1935)

Jane Addams is the first person many look to in order to answer the question “what is social work?”

The eighth of nine children born to a family in Cedarville, Illinois, Jane Addams had a strong sense of social mission starting in childhood. By the age of 21, she had graduated from Rockford Female Seminary and set out to find her path toward helping others. In 1889, Addams and her friend Ellen Gates Starr founded Hull House in Chicago. Hull House became a hub where immigrants could learn skills and trades and where they could benefit from services like childcare, music, art, theater and public baths and kitchen facilities.

Addams also lobbied for legislation that would improve the lives of the poor, such as a juvenile court system, improved city sanitation and better factory laws. She campaigned for labor laws that protected women and for greater access to childcare so that mothers could work to support their families. Her titles were many, including president of the National Conference of Charities and Corrections, officer in the National American Women’s Suffrage Association and co-founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

Addams protested American participation in World War I, headed the Women’s Peace Party, served as president of the International Congress of Women and helped found the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom. In 1931, Addams became the first American woman to receive the Nobel Peace Prize.

The Unsung Hero: George Edmund Haynes (1880 – 1960)

Born in Pine Bluff, Arkansas just fifteen years after the Civil War concluded, George Edmund Haynes dedicated his life to the wellbeing of fellow Black Americans. Haynes wrote his doctoral dissertation The Negro at Work in New York City during his Ph.D. program at Columbia University. Haynes worked with several committees to improve the lives of Black Americans—committees which he helped to merge, creating the National League on Urban Conditions Among Negroes (NLUCAN), now known as the National Urban League.

Haynes’ accomplishments included establishing the Association of Negro Colleges and Secondary Schools, serving as Director of Negro Economics in the United States Department of Labor, working as a Special Assistant to the Secretary of Labor. His unprecedented research made critical strides in the fight against racial discrimination and toward social and economic equality.

Bain News Service. (1917). Jeannette Rankin [Photograph]. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Retrieved from the Library of Congress online database.

The Pacifist Pioneer: Jeannette Rankin (1880 – 1973)

Jeannette Rankin was the first woman to ever be elected to the House of Representatives. As a member of the House of Representatives, Rankin cast the only opposing vote to a motion to declare war on Japan after the Pearl Harbor attack. For Rankin, peace issues and women’s issues were inextricable. Her training and practice as a social worker fueled her sponsorship of legislative bills to allow American women who married foreign nationals to remain citizens and to fund efforts to teach women about sexual health.

After years of campaigning for women’s suffrage, Rankin introduced the Nineteenth Amendment in Congress, campaigning for Woman’s Right to Vote. Later in her life, Rankin worked in foster care, which she determined needed institutional reform. At the age of 88, Rankin was still hard at work, leading a 5000-woman march on Washington to protest the war in Vietnam.

The Model Maker: Harriet Rinaldo (1906 – 1981)

When Harriet Rinaldo was just 23 years old, she had already earned her master’s degree in Social Science. Rinaldo worked for the Children’s Aid Society and county welfare agency in Philadelphia before moving to the Social Security Agency in New York.

Rinaldo transitioned to the Veterans Administration in Washington, DC, where she developed personnel standards, rating procedures and recruitment processes that would become the model for federal government departments and many social work agencies.

Rinaldo’s model making did not stop at organizational policies and procedures. She was also the first person to identify the term “clinical social work,” a designation that is still used to specify a special social work role today.

Abbie Rowe. (1963). Meeting with the leaders of "The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom," 5:00PM [Photograph]. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston, MA. Retrieved from the JFK Library online database.

The Champion for Access: Whitney M. Young, Jr. (1921 – 1971)

Whitney M. Young, Jr. committed his career to eradicating employment discrimination and strengthening the approach of the National Urban League. As executive secretary of the Urban League in Nebraska, Young dedicated himself to helping Black workers secure jobs that had previously been withheld from them. He taught social work at the university level, eventually becoming dean of a social work department.

At the age of 40, Young became the executive director of the National Urban League, a position he held until his death. Under his leadership, the National Urban League became a key organization in the American Civil Rights Movement. Young expanded the group’s mission, grew its membership and budget exponentially and earned the support of Presidents Kennedy, Johnson and Nixon. As the president of the National Association of Social Workers (NASW), Young urged social workers to prioritize reducing poverty, facilitating racial reconciliation and campaigning against the Vietnam War.

The Beloved Visionary: Antonia Pantoja (1922 – 2002)

The founder of ASPIRA, a nonprofit organization dedicated to educational success and long-term wellbeing for Latino youth, Antonia Pantoja is considered one of the most important Puerto Rican American leaders. She served as a social work faculty member and founded the Graduate School of Community Development in San Diego, California.

A co-founder of the National Puerto Rico Forum and Boricua College who was active in a long list of organizations working to strengthen minority communities, Pantoja was described as “the most respected and loved member of the Puerto Rican community.” The person who praised her this way? President Bill Clinton, when he awarded her the Presidential Medal of Freedom the accomplishments of ASPIRA.

The Tireless Trainer: Diana Ming Chan (1929 – 2008)

Diana Ming Chan spent her 54-year career directing, educating and training in just about every way that she could. As the first Cantonese-speaking Chinese MSW in San Francisco Chinatown, Chan was instrumental in developing cultural competence practices that she passed on to many more social workers and organizations. Chan was a staunch champion at the policymaking level for increased numbers of social workers in schools. Ever an educator, Chan not only demonstrated the need for more social workers in schools but presented a plan for funding additional school social workers.

When Chan passed away in 2008, the director of the NASW Foundation described her legacy as follows:

“Although Mrs. Chan died unexpectedly, her work has lived on. She has had a significant and lasting impact on the role and function of school social workers by making certain funding remains in place to provide social workers in schools.”

Join the Legacy of these Social Workers at Florida State

From Addams to Chan and countless others in between, social workers today continue to build on the legacy of those who have made a positive impact on others. Learn more about these remarkable individuals by reading their collected NASW Social Work Pioneers® biographies.

If you find that your mind is racing with ways to empower people and communities just as these historical social workers have, an online Master of Social Work degree from Florida State University can help you realize your ideas.

Florida State University has offered social welfare classes for over 100 years. As the first program of its kind in the United States, the online MSW prepares graduates to answer the question “what do social workers do?’ through their day-to-day work campaigning for the good of others. The program offers two tracks — the two-year Advanced Standing Social Work program for those with a BSW and the three-year Traditional Social Work program for those with a bachelor’s in another area of study.

What better way to celebrate Social Work Month than by learning more about the online MSW from Florida State University? After all, “the time is right for social work.”